Of

all the diving locations in New Zealand, the Three Kings Islands are

often regarded as the best.

Of

all the diving locations in New Zealand, the Three Kings Islands are

often regarded as the best.

Situated approximately 55 kilometres north west of the northern most

tip of New Zealand's North Island, they provide an opportunity to

experience New Zealand's marine environment at it's most raw and beautiful.

Around the islands oceanic currents held

apart for hundreds of kilometres meet eachother and mix in a cauldron

of concentrated marine life. Here the tides are unpredictable, the

currents extreme and the sea conditions often unforgiving.

|

Dive charters to the Three Kings are expensive and demanding of vessel, crew and divers. Most New Zealand divers never get there but for those that do, what must be some of the best temperate water diving on the planet awaits.

Of Skip's five trips to "The Kings" each has fond memories. The following is based on the 1999 trip between 19th and 23rd April.

In

the days leading up to our trip the whole country experienced miserable

weather which resulted in some fairly unfriendly seas being generated.

Off

the top end of New Zealand, these seas were coming from the south

west and by the time our trip was ready to depart on the Sunday afternoon,

the wind had dropped to almost nothing but had left a substantial

south west swell of about 4 metres.

Our departure from Whangaroa was delayed until early Monday morning

in order to give the sea a few extra hours to settle. We arrived at

the Kings early on Monday afternoon and headed straight for the site

of the wreck of the Elingamite. This is located on one of the most

exposed corners of the Kings and was still fairly sloppy due to the

substantial south west swell. Because of conditions, we elected to

give the wreck site a miss until the following morning and had a less

adventurous dive nearby.

Over

the next fours days the weather was magnificent with scarcely any

wind at all and blue, sunny skies. Over this period the south west

swell abated to insignificance and diving conditions on the wreck

site steadily improved.

|

For me the focus of all diving at the Kings is the wreck of the Elingamite. Whenever conditions permit, it is my preferred dive site. As mentioned previously, sea conditions here are often not kind. Apart from the ravages of wind and waves, the current here is often fierce. During periods of strong current the diver in the water is helpless to swim against it in any meaningful way.

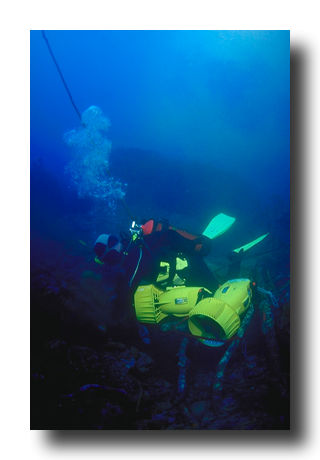

Dives

to the wreck itself therefore employ a shot line which divers use

to guide themselves from the surface to the wreck and to hold themselves

against the current.

The commonly worked areas of the wreck are at a depth of 37 to 39

metres and in order to give an extended time there it is normal to

plan decompression stops on the shot line at 3 to 5 metres depth.

When the current is running strongly, divers are hung out on the shot

line doing their decompression stops like socks to dry on a Wellington

clothes line.

To hang on the shot line like this for periods of up to half an hour

under these conditions isn't too bad but there is always a little

apprehension under such circumstances. As you gaze into the blue,

little questions like "what if I let go and get swept away in the

current", "what if the shot line breaks" or, "what if the buoys get

dragged under" lurk in the back of your mind.

|

Substantial

flotation is required at the top of the shot line in order to ensure

that the line to the surface is maintained under conditions of strong

current with as many as 6 or 8 divers creating drag on it. On a previous

trip, I had experienced the uncomfortable sight of the buoys being

dragged under to a depth of perhaps 8 metres but fortunately they

eventually rose back to the surface.

On one of our dives on this trip the current was particularly fierce

and the flotation provided by the buoys was not sufficient to keep

them on the surface with 6 or 7 seven divers on the line. This resulted

in a very unpleasant predicament for Neil, Simon and myself as we

found ourselves being dragged deeper and deeper as the buoys were

dragged further and further down. We already had an obligation to

spend time decompressing, had a limited amount of air left, and were

being dragged down to over 20 metres depth where our decompression

obligations were getting worse and our air supplies were fast running

out.

We quickly realised that we had no alternative but to let go of the

shot line and rise slowly to the depth where we should be decompressing.

That part was good but we were now being swept out into open water

at 3 or 4 knots and now had no ability to breathe off the spare air

supply tied to the top of the shot line. While we drifted along, Neil

released his tethered safety sausage which rose to the surface and

provided hope that the boat would be aware of our location and predicament.

While all this was happening, anxiety levels were up a notch or two

and air consumption rates had increased accordingly. Almost immediately

after my dive computer indicated that I had spent the necessary time

decompressing, Neil signaled that he was out of air and wanted to

buddy breathe.

|

I

hate buddy breathing! The first few breaths are OK but subsequent

ones seem to have more and more water entrained in them. I had only

enough air left for a few minutes of safety but this was quickly depleted

during the buddy breathing and we were soon forced to surface. Unlike

me, Neil and Simon still had decompression time to do and needed to

quickly get back down to decompression depth. Fortunately, the boat

had seen Neil's safety sausage and were able to pick us up quickly

and rig up a fresh tank for Neil and Simon to continue their decompression

in mid water. While they were doing this, the boat whizzed back to

the shot line and dropped me in on it for a safety stop. After about

half an hour hanging on in the current, the boat had retrieved Neil

and Simon and came back to pick me up. During that dive I got two

lousy silver coins.

In between

dives on the wreck, we had a morning out on the King Bank. This is

located about 14 nautical miles north east of the Kings and is perhaps

the most isolated dive spot in New Zealand. Here, an underwater sea

mount rises from abyssal depths to within diveable limits. On this

day, as on the two previous dives I have done there, the current was

strong and there was little option but to drift with the flow. The

bank rises to a peak of 28 metres but you are quickly swept over this

and can expect to spend most of the dive in over 40 metres depth.

The bottom is fairly flat reef covered sparsely with Eklonia kelp.

Some might call it a boring dive but for me, it's exhilarating. The

fact that you're diving in the middle of nowhere in an area proven

as one of the world's most productive game fishing grounds is enough

to make it special. I've only ever seen reef fish and kingfish here

but the real possibility of swimming with tuna, sharks or marlin would

keep me coming back.

|

Other

classic Kings dives including the Dentist's Cavity, home of a school

of the rare and protected black spotted groper, and Dury's Dream Pipe,

an underwater tunnel lined with gorgonian fans and the special ivory

coral, Oculina virgosa, gave all on board further tastes of

the very special diving that only the Kings can provide.

On our last day at the Kings the wreck site was wonderfully calm.

On previous wreck dives, I had concentrated almost exclusively on

excavating one small hole. From this I had extracted no more than

a few silver coins on each dive. On this last dive I took down my

camera fitted with 16mm fisheye lens with the intention of taking

photos of the wreck site with divers working on it.

On first hitting the bottom, I stuck with the plan and took about

half a dozen shots of Neil working a hole located close to the bottom

of the shot line. After taking a few snaps, I put the camera aside

and started to do a little digging myself. Almost immediately, the

milled edges of silver half crown coins were plainly visible amongst

the encrusted lumps of debris and rock and we soon became almost frenzied

in our attempts is dislodge more and more coins.

A few minutes later, I seized a small pebble of encrusted debris and

on glancing at it, immediately realized I had secured a great prize

; a gold half sovereign. Ecstatic, I showed Neil and stuffed it up

my drysuit wrist seal for safe keeping. Most divers got plenty of

silver coins but this was to be the only gold coin retrieved during

the trip.

|

Neil

and I stretched our bottom time beyond safe limits but frustratingly,

had to begin our ascent to the surface and leave behind several partially

exposed half crowns which we were unable to dislodge. This was to

be our last dive of the trip but others going down after us were given

good instructions and were able to secure those remaining coins.

We departed the Kings at 3 pm on Friday afternoon as the wind from

the east, forecast to arrive at least a day earlier, finally began

to build in strength. As we approached North Cape, darkness descended

and the boat began to take more and more of a pounding.

The wind

and seas built further and for the next few hours I moved constantly

about the boat, trying to find a spot where it felt safe, where it

felt like the boat wasn't about to fall apart. Eventually,

eight hours after departing West King Island we finally made the lee

of Stephenson Island and soon crept back into the haven of Whangaroa

harbour.

© 1999-2000

ianskipworth.com